library(tensorflow)Introduction to Tensors

Learn about Tensors, the multi-dimensional arrays used by TensorFlow.

Tensors are multi-dimensional arrays with a uniform type (called a dtype). You can see all supported dtypes with names(tf$dtypes).

If you’re familiar with R array or NumPy, tensors are (kind of) like R or NumPy arrays.

All tensors are immutable: you can never update the contents of a tensor, only create a new one.

Basics

Let’s create some basic tensors.

Here is a “scalar” or “rank-0” tensor . A scalar contains a single value, and no “axes”.

# This will be an float64 tensor by default; see "dtypes" below.

rank_0_tensor <- as_tensor(4)

print(rank_0_tensor)tf.Tensor(4.0, shape=(), dtype=float64)A “vector” or “rank-1” tensor is like a list of values. A vector has one axis:

rank_1_tensor <- as_tensor(c(2, 3, 4))

print(rank_1_tensor)tf.Tensor([2. 3. 4.], shape=(3), dtype=float64)A “matrix” or “rank-2” tensor has two axes:

# If you want to be specific, you can set the dtype (see below) at creation time

rank_2_tensor <-

as_tensor(rbind(c(1, 2),

c(3, 4),

c(5, 6)),

dtype=tf$float16)

print(rank_2_tensor)tf.Tensor(

[[1. 2.]

[3. 4.]

[5. 6.]], shape=(3, 2), dtype=float16)A scalar, shape: [] |

A vector, shape: [3] |

A matrix, shape: [3, 2] |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Tensors may have more axes; here is a tensor with three axes:

# There can be an arbitrary number of

# axes (sometimes called "dimensions")

rank_3_tensor <- as_tensor(0:29, shape = c(3, 2, 5))

rank_3_tensortf.Tensor(

[[[ 0 1 2 3 4]

[ 5 6 7 8 9]]

[[10 11 12 13 14]

[15 16 17 18 19]]

[[20 21 22 23 24]

[25 26 27 28 29]]], shape=(3, 2, 5), dtype=int32)There are many ways you might visualize a tensor with more than two axes.

A 3-axis tensor, shape: [3, 2, 5] |

|---|

! !   |

You can convert a tensor to an R array using as.array():

as.array(rank_2_tensor) [,1] [,2]

[1,] 1 2

[2,] 3 4

[3,] 5 6Tensors often contain floats and ints, but have many other types, including:

- complex numbers

- strings

The base tf$Tensor class requires tensors to be “rectangular”—that is, along each axis, every element is the same size. However, there are specialized types of tensors that can handle different shapes:

- Ragged tensors (see RaggedTensor below)

- Sparse tensors (see SparseTensor below)

You can do basic math on tensors, including addition, element-wise multiplication, and matrix multiplication.

a <- as_tensor(1:4, shape = c(2, 2))

b <- as_tensor(1L, shape = c(2, 2))

a + b # element-wise addition, same as tf$add(a, b)tf.Tensor(

[[2 3]

[4 5]], shape=(2, 2), dtype=int32)a * b # element-wise multiplication, same as tf$multiply(a, b)tf.Tensor(

[[1 2]

[3 4]], shape=(2, 2), dtype=int32)tf$matmul(a, b) # matrix multiplicationtf.Tensor(

[[3 3]

[7 7]], shape=(2, 2), dtype=int32)Tensors are used in all kinds of operations (ops).

x <- as_tensor(rbind(c(4, 5), c(10, 1)))

# Find the largest value

# Find the largest value

tf$reduce_max(x) # can also just call max(c)tf.Tensor(10.0, shape=(), dtype=float64)# Find the index of the largest value

tf$math$argmax(x) tf.Tensor([1 0], shape=(2), dtype=int64)tf$nn$softmax(x) # Compute the softmaxtf.Tensor(

[[2.68941421e-01 7.31058579e-01]

[9.99876605e-01 1.23394576e-04]], shape=(2, 2), dtype=float64)About shapes

Tensors have shapes. Some vocabulary:

- Shape: The length (number of elements) of each of the axes of a tensor.

- Rank: Number of tensor axes. A scalar has rank 0, a vector has rank 1, a matrix is rank 2.

- Axis or Dimension: A particular dimension of a tensor.

- Size: The total number of items in the tensor, the product of the shape vector’s elements.

Note: Although you may see reference to a “tensor of two dimensions”, a rank-2 tensor does not usually describe a 2D space.

Tensors and tf$TensorShape objects have convenient properties for accessing these:

rank_4_tensor <- tf$zeros(shape(3, 2, 4, 5))A rank-4 tensor, shape: [3, 2, 4, 5] |

|---|

|

message("Type of every element: ", rank_4_tensor$dtype)Type of every element: <dtype: 'float32'>message("Number of axes: ", length(dim(rank_4_tensor)))Number of axes: 4message("Shape of tensor: ", dim(rank_4_tensor)) # can also access via rank_4_tensor$shapeShape of tensor: 3245message("Elements along axis 0 of tensor: ", dim(rank_4_tensor)[1])Elements along axis 0 of tensor: 3message("Elements along the last axis of tensor: ", dim(rank_4_tensor) |> tail(1)) Elements along the last axis of tensor: 5message("Total number of elements (3*2*4*5): ", length(rank_4_tensor)) # can also call tf$size()Total number of elements (3*2*4*5): 120While axes are often referred to by their indices, you should always keep track of the meaning of each. Often axes are ordered from global to local: The batch axis first, followed by spatial dimensions, and features for each location last. This way feature vectors are contiguous regions of memory.

| Typical axis order |

|---|

|

Indexing

Single-axis indexing

See ?`[.tensorflow.tensor` for details

Multi-axis indexing

Higher rank tensors are indexed by passing multiple indices.

The exact same rules as in the single-axis case apply to each axis independently.

Read the tensor slicing guide to learn how you can apply indexing to manipulate individual elements in your tensors.

Manipulating Shapes

Reshaping a tensor is of great utility.

# Shape returns a `TensorShape` object that shows the size along each axis

x <- as_tensor(1:3, shape = c(1, -1))

x$shapeTensorShape([1, 3])# You can convert this object into an R vector too

as.integer(x$shape)[1] 1 3You can reshape a tensor into a new shape. The tf$reshape operation is fast and cheap as the underlying data does not need to be duplicated.

# You can reshape a tensor to a new shape.

# Note that you're passing in integers

reshaped <- tf$reshape(x, c(1L, 3L))x$shapeTensorShape([1, 3])reshaped$shapeTensorShape([1, 3])The data maintains its layout in memory and a new tensor is created, with the requested shape, pointing to the same data. TensorFlow uses C-style “row-major” memory ordering, where incrementing the rightmost index corresponds to a single step in memory.

rank_3_tensortf.Tensor(

[[[ 0 1 2 3 4]

[ 5 6 7 8 9]]

[[10 11 12 13 14]

[15 16 17 18 19]]

[[20 21 22 23 24]

[25 26 27 28 29]]], shape=(3, 2, 5), dtype=int32)If you flatten a tensor you can see what order it is laid out in memory.

# A `-1` passed in the `shape` argument says "Whatever fits".

tf$reshape(rank_3_tensor, c(-1L))tf.Tensor(

[ 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23

24 25 26 27 28 29], shape=(30), dtype=int32)A typical and reasonable use of tf$reshape is to combine or split adjacent axes (or add/remove 1s).

For this 3x2x5 tensor, reshaping to (3x2)x5 or 3x(2x5) are both reasonable things to do, as the slices do not mix:

tf$reshape(rank_3_tensor, as.integer(c(3*2, 5)))tf.Tensor(

[[ 0 1 2 3 4]

[ 5 6 7 8 9]

[10 11 12 13 14]

[15 16 17 18 19]

[20 21 22 23 24]

[25 26 27 28 29]], shape=(6, 5), dtype=int32)tf$reshape(rank_3_tensor, as.integer(c(3L, -1L)))tf.Tensor(

[[ 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9]

[10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19]

[20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29]], shape=(3, 10), dtype=int32)| Some good reshapes. |

|---|

|

https://www.tensorflow.org/guide/images/tensor/reshape-before.png https://www.tensorflow.org/guide/ https://www.tensorflow.org/guide/images/tensor/reshape-good2.png

Reshaping will “work” for any new shape with the same total number of elements, but it will not do anything useful if you do not respect the order of the axes.

Swapping axes in tf$reshape does not work; you need tf$transpose for that.

# Bad examples: don't do this

# You can't reorder axes with reshape.

tf$reshape(rank_3_tensor, as.integer(c(2, 3, 5)))tf.Tensor(

[[[ 0 1 2 3 4]

[ 5 6 7 8 9]

[10 11 12 13 14]]

[[15 16 17 18 19]

[20 21 22 23 24]

[25 26 27 28 29]]], shape=(2, 3, 5), dtype=int32)# This is a mess

tf$reshape(rank_3_tensor, as.integer(c(5, 6)))tf.Tensor(

[[ 0 1 2 3 4 5]

[ 6 7 8 9 10 11]

[12 13 14 15 16 17]

[18 19 20 21 22 23]

[24 25 26 27 28 29]], shape=(5, 6), dtype=int32)# This doesn't work at all

try(tf$reshape(rank_3_tensor, as.integer(c(7, -1))))Error in py_call_impl(callable, dots$args, dots$keywords) :

tensorflow.python.framework.errors_impl.InvalidArgumentError: {{function_node __wrapped__Reshape_device_/job:localhost/replica:0/task:0/device:GPU:0}} Input to reshape is a tensor with 30 values, but the requested shape requires a multiple of 7 [Op:Reshape]| Some bad reshapes. |

|---|

|

You may run across not-fully-specified shapes. Either the shape contains a NULL (an axis-length is unknown) or the whole shape is NULL (the rank of the tensor is unknown).

Except for tf$RaggedTensor, such shapes will only occur in the context of TensorFlow’s symbolic, graph-building APIs:

More on DTypes

To inspect a tf$Tensor’s data type use the Tensor$dtype property.

When creating a tf$Tensor from a Python object you may optionally specify the datatype.

If you don’t, TensorFlow chooses a datatype that can represent your data. TensorFlow converts R integers to tf$int32 and R floating point numbers to tf$float64.

You can cast from type to type.

the_f64_tensor <- as_tensor(c(2.2, 3.3, 4.4), dtype = tf$float64)

the_f16_tensor <- tf$cast(the_f64_tensor, dtype = tf$float16)

# Now, cast to an uint8 and lose the decimal precision

the_u8_tensor <- tf$cast(the_f16_tensor, dtype = tf$uint8)

the_u8_tensortf.Tensor([2 3 4], shape=(3), dtype=uint8)Broadcasting

Broadcasting is a concept borrowed from the equivalent feature in NumPy. In short, under certain conditions, smaller tensors are recycled automatically to fit larger tensors when running combined operations on them.

The simplest and most common case is when you attempt to multiply or add a tensor to a scalar. In that case, the scalar is broadcast to be the same shape as the other argument.

x <- as_tensor(c(1, 2, 3))

y <- as_tensor(2)

z <- as_tensor(c(2, 2, 2))

# All of these are the same computation

tf$multiply(x, 2)tf.Tensor([2. 4. 6.], shape=(3), dtype=float64)x * ytf.Tensor([2. 4. 6.], shape=(3), dtype=float64)x * ztf.Tensor([2. 4. 6.], shape=(3), dtype=float64)Likewise, axes with length 1 can be stretched out to match the other arguments. Both arguments can be stretched in the same computation.

In this case a 3x1 matrix is element-wise multiplied by a 1x4 matrix to produce a 3x4 matrix. Note how the leading 1 is optional: The shape of y is [4].

# These are the same computations

(x <- tf$reshape(x, as.integer(c(3, 1))))tf.Tensor(

[[1.]

[2.]

[3.]], shape=(3, 1), dtype=float64)(y <- tf$range(1, 5, dtype = "float64"))tf.Tensor([1. 2. 3. 4.], shape=(4), dtype=float64)x * ytf.Tensor(

[[ 1. 2. 3. 4.]

[ 2. 4. 6. 8.]

[ 3. 6. 9. 12.]], shape=(3, 4), dtype=float64)A broadcasted add: a [3, 1] times a [1, 4] gives a [3,4] |

|---|

\ \ |

Here is the same operation without broadcasting:

x_stretch <- as_tensor(rbind(c(1, 1, 1, 1),

c(2, 2, 2, 2),

c(3, 3, 3, 3)))

y_stretch <- as_tensor(rbind(c(1, 2, 3, 4),

c(1, 2, 3, 4),

c(1, 2, 3, 4)))

x_stretch * y_stretch tf.Tensor(

[[ 1. 2. 3. 4.]

[ 2. 4. 6. 8.]

[ 3. 6. 9. 12.]], shape=(3, 4), dtype=float64)Most of the time, broadcasting is both time and space efficient, as the broadcast operation never materializes the expanded tensors in memory.

You see what broadcasting looks like using tf$broadcast_to.

tf$broadcast_to(as_tensor(c(1, 2, 3)), c(3L, 3L))tf.Tensor(

[[1. 2. 3.]

[1. 2. 3.]

[1. 2. 3.]], shape=(3, 3), dtype=float64)Unlike a mathematical op, for example, broadcast_to does nothing special to save memory. Here, you are materializing the tensor.

It can get even more complicated. This section of Jake VanderPlas’s book Python Data Science Handbook shows more broadcasting tricks (again in NumPy).

tf$convert_to_tensor

Most ops, like tf$matmul and tf$reshape take arguments of class tf$Tensor. However, you’ll notice in the above case, objects shaped like tensors are also accepted.

Most, but not all, ops call convert_to_tensor on non-tensor arguments. There is a registry of conversions, and most object classes like NumPy’s ndarray, TensorShape, Python lists, and tf$Variable will all convert automatically.

See tf$register_tensor_conversion_function for more details, and if you have your own type you’d like to automatically convert to a tensor.

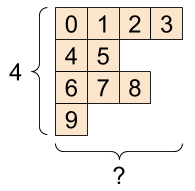

Ragged Tensors

A tensor with variable numbers of elements along some axis is called “ragged”. Use tf$ragged$RaggedTensor for ragged data.

For example, This cannot be represented as a regular tensor:

A tf$RaggedTensor, shape: [4, NULL] |

|---|

|

ragged_list <- list(list(0, 1, 2, 3),

list(4, 5),

list(6, 7, 8),

list(9))try(tensor <- as_tensor(ragged_list))Error in py_call_impl(callable, dots$args, dots$keywords) :

ValueError: Can't convert non-rectangular Python sequence to Tensor.Instead create a tf$RaggedTensor using tf$ragged$constant:

(ragged_tensor <- tf$ragged$constant(ragged_list))<tf.RaggedTensor [[0.0, 1.0, 2.0, 3.0], [4.0, 5.0], [6.0, 7.0, 8.0], [9.0]]>The shape of a tf$RaggedTensor will contain some axes with unknown lengths:

print(ragged_tensor$shape)TensorShape([4, None])String tensors

tf$string is a dtype, which is to say you can represent data as strings (variable-length byte arrays) in tensors.

The length of the string is not one of the axes of the tensor. See tf$strings for functions to manipulate them.

Here is a scalar string tensor:

# Tensors can be strings, too here is a scalar string.

(scalar_string_tensor <- as_tensor("Gray wolf"))tf.Tensor(b'Gray wolf', shape=(), dtype=string)And a vector of strings:

A vector of strings, shape: [3,] |

|---|

|

tensor_of_strings <- as_tensor(c("Gray wolf",

"Quick brown fox",

"Lazy dog"))

# Note that the shape is (3). The string length is not included.

tensor_of_stringstf.Tensor([b'Gray wolf' b'Quick brown fox' b'Lazy dog'], shape=(3), dtype=string)In the above printout the b prefix indicates that tf$string dtype is not a unicode string, but a byte-string. See the Unicode Tutorial for more about working with unicode text in TensorFlow.

If you pass unicode characters they are utf-8 encoded.

as_tensor("🥳👍")tf.Tensor(b'\xf0\x9f\xa5\xb3\xf0\x9f\x91\x8d', shape=(), dtype=string)Some basic functions with strings can be found in tf$strings, including tf$strings$split.

# You can use split to split a string into a set of tensors

tf$strings$split(scalar_string_tensor, sep=" ")tf.Tensor([b'Gray' b'wolf'], shape=(2), dtype=string)# ...and it turns into a `RaggedTensor` if you split up a tensor of strings,

# as each string might be split into a different number of parts.

tf$strings$split(tensor_of_strings)<tf.RaggedTensor [[b'Gray', b'wolf'], [b'Quick', b'brown', b'fox'], [b'Lazy', b'dog']]>Three strings split, shape: [3, NULL] |

|---|

|

And tf$string$to_number:

text <- as_tensor("1 10 100")

tf$strings$to_number(tf$strings$split(text, " "))tf.Tensor([ 1. 10. 100.], shape=(3), dtype=float32)Although you can’t use tf$cast to turn a string tensor into numbers, you can convert it into bytes, and then into numbers.

byte_strings <- tf$strings$bytes_split(as_tensor("Duck"))

byte_ints <- tf$io$decode_raw(as_tensor("Duck"), tf$uint8)

cat("Byte strings: "); print(byte_strings)Byte strings: tf.Tensor([b'D' b'u' b'c' b'k'], shape=(4), dtype=string)cat("Bytes: "); print(byte_ints)Bytes: tf.Tensor([ 68 117 99 107], shape=(4), dtype=uint8)# Or split it up as unicode and then decode it

unicode_bytes <- as_tensor("アヒル 🦆")

unicode_char_bytes <- tf$strings$unicode_split(unicode_bytes, "UTF-8")

unicode_values <- tf$strings$unicode_decode(unicode_bytes, "UTF-8")

cat("Unicode bytes: "); unicode_bytesUnicode bytes: tf.Tensor(b'\xe3\x82\xa2\xe3\x83\x92\xe3\x83\xab \xf0\x9f\xa6\x86', shape=(), dtype=string)cat("Unicode chars: "); unicode_char_bytesUnicode chars: tf.Tensor([b'\xe3\x82\xa2' b'\xe3\x83\x92' b'\xe3\x83\xab' b' ' b'\xf0\x9f\xa6\x86'], shape=(5), dtype=string)cat("Unicode values: "); unicode_valuesUnicode values: tf.Tensor([ 12450 12498 12523 32 129414], shape=(5), dtype=int32)The tf$string dtype is used for all raw bytes data in TensorFlow. The tf$io module contains functions for converting data to and from bytes, including decoding images and parsing csv.

Sparse tensors

Sometimes, your data is sparse, like a very wide embedding space. TensorFlow supports tf$sparse$SparseTensor and related operations to store sparse data efficiently.

A tf$SparseTensor, shape: [3, 4] |

|---|

|

# Sparse tensors store values by index in a memory-efficient manner

sparse_tensor <- tf$sparse$SparseTensor(

indices = rbind(c(0L, 0L),

c(1L, 2L)),

values = c(1, 2),

dense_shape = as.integer(c(3, 4))

)

sparse_tensorSparseTensor(indices=tf.Tensor(

[[0 0]

[1 2]], shape=(2, 2), dtype=int64), values=tf.Tensor([1. 2.], shape=(2), dtype=float32), dense_shape=tf.Tensor([3 4], shape=(2), dtype=int64))# You can convert sparse tensors to dense

tf$sparse$to_dense(sparse_tensor)tf.Tensor(

[[1. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 2. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0.]], shape=(3, 4), dtype=float32)Environment Details

tensorflow::tf_config()TensorFlow v2.11.0 (~/.virtualenvs/r-tensorflow-website/lib/python3.10/site-packages/tensorflow)

Python v3.10 (~/.virtualenvs/r-tensorflow-website/bin/python)sessionInfo()R version 4.2.1 (2022-06-23)

Platform: x86_64-pc-linux-gnu (64-bit)

Running under: Ubuntu 20.04.5 LTS

Matrix products: default

BLAS: /home/tomasz/opt/R-4.2.1/lib/R/lib/libRblas.so

LAPACK: /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libmkl_intel_lp64.so

locale:

[1] LC_CTYPE=en_US.UTF-8 LC_NUMERIC=C

[3] LC_TIME=en_US.UTF-8 LC_COLLATE=en_US.UTF-8

[5] LC_MONETARY=en_US.UTF-8 LC_MESSAGES=en_US.UTF-8

[7] LC_PAPER=en_US.UTF-8 LC_NAME=C

[9] LC_ADDRESS=C LC_TELEPHONE=C

[11] LC_MEASUREMENT=en_US.UTF-8 LC_IDENTIFICATION=C

attached base packages:

[1] stats graphics grDevices utils datasets methods base

other attached packages:

[1] tensorflow_2.9.0.9000

loaded via a namespace (and not attached):

[1] Rcpp_1.0.9 whisker_0.4.1 knitr_1.41

[4] magrittr_2.0.3 here_1.0.1 lattice_0.20-45

[7] rlang_1.0.6 fastmap_1.1.0 fansi_1.0.3

[10] stringr_1.5.0 tools_4.2.1 grid_4.2.1

[13] xfun_0.35 png_0.1-8 utf8_1.2.2

[16] cli_3.4.1 tfruns_1.5.1 htmltools_0.5.4

[19] rprojroot_2.0.3 yaml_2.3.6 digest_0.6.31

[22] tibble_3.1.8 lifecycle_1.0.3 Matrix_1.5-3

[25] base64enc_0.1-3 htmlwidgets_1.5.4 vctrs_0.5.1

[28] glue_1.6.2 evaluate_0.18 rmarkdown_2.18

[31] stringi_1.7.8 compiler_4.2.1 pillar_1.8.1

[34] reticulate_1.26-9000 jsonlite_1.8.4 pkgconfig_2.0.3 system2(reticulate::py_exe(), c("-m pip freeze"), stdout = TRUE) |> writeLines()absl-py==1.3.0

asttokens==2.2.1

astunparse==1.6.3

backcall==0.2.0

cachetools==5.2.0

certifi==2022.12.7

charset-normalizer==2.1.1

decorator==5.1.1

dill==0.3.6

etils==0.9.0

executing==1.2.0

flatbuffers==22.12.6

gast==0.4.0

google-auth==2.15.0

google-auth-oauthlib==0.4.6

google-pasta==0.2.0

googleapis-common-protos==1.57.0

grpcio==1.51.1

h5py==3.7.0

idna==3.4

importlib-resources==5.10.1

ipython==8.7.0

jedi==0.18.2

kaggle==1.5.12

keras==2.11.0

keras-tuner==1.1.3

kt-legacy==1.0.4

libclang==14.0.6

Markdown==3.4.1

MarkupSafe==2.1.1

matplotlib-inline==0.1.6

numpy==1.23.5

oauthlib==3.2.2

opt-einsum==3.3.0

packaging==22.0

pandas==1.5.2

parso==0.8.3

pexpect==4.8.0

pickleshare==0.7.5

Pillow==9.3.0

promise==2.3

prompt-toolkit==3.0.36

protobuf==3.19.6

ptyprocess==0.7.0

pure-eval==0.2.2

pyasn1==0.4.8

pyasn1-modules==0.2.8

pydot==1.4.2

Pygments==2.13.0

pyparsing==3.0.9

python-dateutil==2.8.2

python-slugify==7.0.0

pytz==2022.6

PyYAML==6.0

requests==2.28.1

requests-oauthlib==1.3.1

rsa==4.9

scipy==1.9.3

six==1.16.0

stack-data==0.6.2

tensorboard==2.11.0

tensorboard-data-server==0.6.1

tensorboard-plugin-wit==1.8.1

tensorflow==2.11.0

tensorflow-datasets==4.7.0

tensorflow-estimator==2.11.0

tensorflow-hub==0.12.0

tensorflow-io-gcs-filesystem==0.28.0

tensorflow-metadata==1.12.0

termcolor==2.1.1

text-unidecode==1.3

toml==0.10.2

tqdm==4.64.1

traitlets==5.7.1

typing_extensions==4.4.0

urllib3==1.26.13

wcwidth==0.2.5

Werkzeug==2.2.2

wrapt==1.14.1

zipp==3.11.0TF Devices:

- PhysicalDevice(name='/physical_device:CPU:0', device_type='CPU')

- PhysicalDevice(name='/physical_device:GPU:0', device_type='GPU')

CPU cores: 12

Date rendered: 2022-12-16

Page render time: 5 seconds